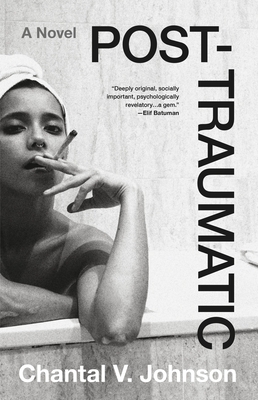

Book Review: Post-Traumatic

Book Reviewed by Robert Fleming

Chantal Johnson’s debut novel, Post-Traumatic, confronts the emotional toll of sexual assault, a real-life survivor narrative, with the prickly residue of mental demons. Her main character, Vivian is a lawyer who advocates for those deemed deranged at a New York City psychiatric facility. This confidant, smart attorney, a hip 30-something, believes the state is the enemy of the people, convinced that profit and power are designed to keep patients off-balanced and helpless. Also, she believes the doctors and nurses want to keep the ill inside the institution and her job is to get them out, to provide expertise for them to avoid the iron grip of the hospital.

Usually, the tough issue of rape is a staple of crime fiction or memoir, but this is the rare work of fiction that tackles sexual violence in the African American community, beyond the gritty streets of the ghetto. Black women are often the forgotten survivors of rape. The National Center on Violence Against Women details four grim statistics, in the Black Community, on this topic: for every Black woman who reports rape, at least 15 Black women do not report; one in four Black girls will be sexually abused before the age of 18; one in five Black women are survivors of rape, and thirty-five percent of Black women experienced some form of contact sexual violence during their lifetime. With all of these facts under her belt, Johnson creates a modern Black woman struggling to fight the toxic effects of rape from warping her consciousness.

Following the downer that is her job, Vivian tries to shake off the entanglements with her troubled clients, meeting up wither bestie, Jane, an old friend from law school. The women get high and trade tales of their survival from childhood sexual abuse. The unruly duo embraces the painful trauma of their rape with dark humor: “They felt united together against everyone else, and considered themselves The only People Talking About Rape, the Only People Brave Enough to Mention Rape Indiscriminately Whether in a Classroom or at Parties, in a Crowded Café or Your Grandmother’s Living Room While Everyone Else in the World is Completely Useless in this Area.”

Written in the third person, the closeness of her character resembles the reader spying and eavesdropping on her every action and word. It was like there was a listening device inside her head. “She had a sensation that she was being filmed,” Johnson writes. “The camera recorded two selves: a self that was limping and wearing a face of cheerless efficiency, and an identical self, defensively crouched and shaking against the wall, watching the other struggle to walk.”

Vivian, from a working-class family, judges other women harshly. She watches women, mostly white women, with distrust and suspicion. Although she follows the feminist playbook much of the time, she says there should be no competition among women, believing it was “a dangerous waste of our time.”

Dating is a problem for Vivian. Every pairing ends up as a flame-out, a bust with snide remarks thrown back and forth, rather than passionate kisses. She is an expert but she often gets a man who refuses to end a relationship “honestly rather than slowly fade away or gaslight her into thinking her insecurities were unfounded.”

It is a difficult journey for Black and Brown professional women. In this book, Vivian turns her back on men of color and seeks out a certain kind of male, mainly financially secure or artistic whites, allowing her to take an aggressive role in the bedroom. She becomes a mistress of the art of orgasm and climax, with a few twisted moments of mayhem and fetish.

“But she soon learned that dating as a Black woman in your thirties was like running a marathon through a swamp wearing steel-toed boots,” Johnson writes about Vivian’s jumbled love life.

Vivian and Paula, a panel psychologist, go to a bar where the white woman drinks too much. She doesn’t want to leave, instead launching into a string of tipsy chatter. She confesses that she used to work at another public hospital in the city. The ignorant talk rambles on and on. “Every day it’s the same. Poor, neglected, abused, poor, neglected, abused,” she slurs. Vivian thinks: This is why you can’t hang out with white women.

At work, Vivian’s empathy for her clients compels her to go against the authority of the facility, making an enemies’ list of those who she does not like. She enters the lives of the inmates and wears herself out fighting their battles until her frustrations and panic attacks render her skills almost useless. Her work is meaningless. She becomes a picky eater, sometimes missing meals. She realizes she is losing control, her traumatized mind slowly shutting down, unable to separate fact from fiction.

Deep in her trauma and mental disorder is her dysfunctional family front and center, with her fickle Puerto Rican mother, Anita, and her many boyfriends. Her brother, Michael, loves to rumble with the old lady and often leaves the house in a huff. Vivian thinks her family is insane. It all blows up at the family reunion when old memories emerge of taking things the wrong way, being humorless, for being antisocial, and thinking you’re better than us with your white words and phrases. In the end, she walks away from the pettiness and vulgarity of her clan, determined to get herself mentally together.

A brilliant chapter, “Vivian At The Wedding,” is Johnson at her best. The Florida Gold Coast setting provides the perfect backdrop at the nuptials for Vivian’s zany antics when she gets Pauline high into the stratosphere on this killer weed, and seduces her hubby, Elliott. She worries that someone at the ceremony had called the police on her. The book offers no resolutions or answers, just an open-ended situation, almost like life itself.

Post-Traumatic is an excellent example of the trauma novel. Its author convinces the reader to identify with Vivian, revealing the truths of her behavior and talk. When she falls apart, it’s almost like you’re seeing it in slow motion, making the reader uneasy and uncomfortable but unable to look away, like a witness to a horrible car crash. This book will take you through all of the emotions piled on top of a terrific trauma arising from uncontrolled lust and desire. If you dare, witness how a modern Black woman dances through the raindrops, through her sadness and confusion, all done with a multitude of scars around her heart and soul. It’s a stylishly funny, original, and thought-provoking book. I can’t wait to see her next creation.