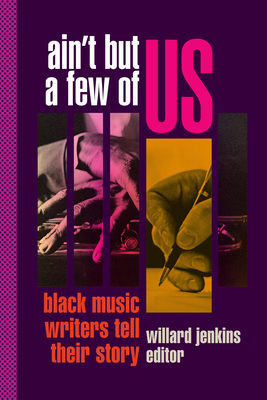

Book Review: Ain’t But a Few of Us: Black Music Writers Tell Their Story

Book Reviewed by Robert Fleming

Jazz is dead! If you believe that mess, you must not listen to radio or read any of the mainstream media. However, the small army of sound warriors have pledged to keep the art form alive despite overwhelming odds.

Willard Jenkins, the artistic director of the DC Jazz Festival, and an art consultant, producer, educator, and journalist, has put the history of these Black music writers on record with his fact-filled book, Ain’t But A Few Of Us Left. Unfortunately, most of the major writers have been traditionally white men like Leonard Feather, Ira Gitler, Gary Giddens, and Lee Jeske. There was no doubt that these critics loved the music but some key ingredients were lacking. As a remedy, the Black literary resistance, a band of race-proud scribes have published essential criticism and analysis on the music, including Amiri Baraka (Leroi Jones), A.B. Spellman, Larry Neal, Ralph Ellison, and Albert Murray. Their works provided a strong foundation for the next generations that followed. Still, Jenkins wanted to question why there were no more Black writers involved. As the author asked, where are the Black writers? The title of this book came from a statement from jazz vibist Milt Jackson to saxophonist Jimmy Heath: “Ain’t but a few of us left.” That quote meant the dwindling number of the Old School jazz musicians, but here Jenkins highlights the shrinking population of Black jazz writers.

The themes of the book are not glossed over lightly, instead the editor presents roundtable discussions, revealing profiles of Black jazz magazine editors and publishers, veteran writers, freelancers, newspaper writers and columnists, and newbies in the business. The writers probed the business and opportunities of promoting jazz, while struggling to have a potent, enlightened voice.

The fact remains that there is no mainstream publication that has had a Black editor or regular jazz columnist, according to the editor. Look around and count the writers commenting on this precious music. Jenkins also noted that the Johnson publications — Ebony and Jet — rarely covered jazz adequately. Like myself who started as a jazz columnist with Cleveland’s weekly music publication, my first regular writing gig, most of the jazz writers hired on to the small, meagerly financed publications or started their own magazines.

The subversive element, who decided not to go along with the status quo about endorsing the lurid myths about the music which came from the folkways of New Orleans. Those in the know began to look for the in-depth criticism of the latter-day Black stylists such as Ron Welburn, Stanley Crouch, Nelson George, Vernon Gibbs, Don Palmer, David Jackson, and Greg Tate. These writers wrote with their heart and soul and gave no quarter.

This is not a Get Whitey diatribe, according to Jenkins. “This book is decidedly not a series of grievances or perceived wrongs, this is more about Black music writers speaking to their journeys and some of the occasional peculiarities related to their experience that certainly in their perception had much to do much about race. None of these writers come off as embittered.”

Jenkins, whose work has appeared in domestic and foreign publications such as Downbeat, JazzTimes and Jazz Forum. In Cleveland, he was exposed to a jazz-loving family, with his father, a veteran newspaperman collecting a jazz vinyl library. He wrote about such acts as Miles, Mingus, Weather Report, Return to Forever, Herbie Hancock, and Sun Ra in locally. Following his father’s introduction to Bob Roach, of Cleveland’s Plain Dealer’s Friday Magazine, he departed his social service career in 1983 to take a promising gig with the Great Lakes Arts Alliance. He relocated to Washington, D.C., assuming the position of executive director of National Jazz Service Organization. Also, he started broadcasting on radio station WPFW-FM.

His even-handed approach to the music and the critics is reflected at the end of this volume which illuminates the vibrant music and the select few who represents it. Readers will delight in the collection of controversial, enlightened essays such as Leroi Jones’ 1966 Downbeat piece on jazz and white critics; Barbara Gardner’s 1963 view of pianist Horace Silver; A. B. Spellman’s 1965 “Trane at the Gate;” Stanley Crouch’s 2003 “Putting the White Man in Charge;” Ron Wynn’s 2013 “Where’s the Black Audience?;” Wayne Shorter’s 1968 “Creativity and Change;” and Archie Sheep’s 1965 “An Artist Speaks Bluntly.” All of these pieces, including others by Ron Welburn, Playthell Benjamin, and Greg Tate, are treasured classics.

After reading the Jenkins book, I came across a segment from the author-editor that he viewed the various online outlets are providing more writers to publish their work.

The barriers of entry are more about opportunity and vehicles. As you know, writing about jazz and opportunities to write about jazz are not as prominent in our prints or on online as are speculations about what Kim Kardashian is doing or what Beyonce wore to the Met Gala. However, the online universe is serving a more diverse cadre of writer who no longer have to sit around awaiting the next assignment from a hard copy publication and can seize opportunities to report on things that strike them as important.

In his life, in his noted career of promotion and criticism, Willard Jenkins is an absolute original. He turned a hobby into a profitable vocation, as he would say. One of the treasures he has produced is his collaboration with pianist Randy Weston’s memoir, African Rhythms, and now this splendid collection, Ain’t But A Few Of Us Left. For jazz buffs and those interested in American culture, this is a spellbinding read and quite impossible to put down. This is an open invitation for the curious wanting an aural adventure.

"